Hajichi: The Forbidden Ink of Ryukyuan Women

How tattoos became a battleground of memory, gender, and resistance under Japanese colonization

Before it was renamed and absorbed into Japan, the Ryukyu Kingdom thrived as a maritime culture with deep spiritual roots and distinct traditions. Among its most profound was Hajichi (針突) — a tattooing practice carried by Ryukyuan women for centuries, literally written on the skin in lines of beauty, power, and ancestral protection.

Today, these marks have all but vanished from living bodies. But the story they tell — of erasure, resilience, and reclamation — is far from over.

⏾Tattoo as Rite, Tattoo as Resistance

Hajichi of the Ryukyu and Amami Islands as drawn by Kamakura Yoshitarō, 1921 (Taisho 10 era). Source: Kamakura Yoshitarō’s materials, housed at Okinawa Prefectural University of Arts Library & Art Archives. Regional Tattoo Labels (From top to bottom, left to right): 1. Kume Island (久米島の入墨)

Tattoo from Kume Island 2. Imaji (今帰仁の入墨) 3.Tattoo from Nakijin (Northern Okinawa) Ihiyazu Island (伊平屋島の入墨) 4. Tattoo from Iheya Island Yoron Island (与論島の入墨) 5. Tattoo from Yoron Island Yonaguni Island (与那国島の入墨) 6. Tattoo from Yonaguni Island Okinawa Island South (沖永良部島の入墨) 7. Tattoo from Okinoerabu Island Kikaijima (喜界島の入墨) 8. Tattoo from Kikaijima Amami Oshima (奄美大島 笠利の入墨) 9.Tattoo from Kasari (Amami Ōshima) Tokunoshima (徳之島の入墨)

10. Tattoo from Tokunoshima Ishigaki Island (石垣島の入墨) 11. Tattoo from Ishigaki Island Miyako Island (宮古島の入墨) 12. Tattoo from Miyako Island Itoman (糸満の入墨) 12. Tattoo from Itoman Shuri (首里の入墨) 13. Tattoo from Shuri (the royal capital of Ryukyu Kingdom) Gushikawa (玉城の入墨) 14. Tattoo from Tamagusuku (modern-day part of Nanjo city)

Hajichi was not just decorative. It was sacred, personal, and political.

Women received their first tattoos between the ages of 4 and 13, gradually completing them around marriage age. The designs — primarily on the backs of the hands, fingers, and wrists — served as rites of passage, symbols of womanhood, and spiritual safeguards. Without Hajichi, it was believed, a woman could not enter the afterlife or properly protect her home.

The patterns varied across the Ryukyu Islands — from Amami to Miyako to Yaeyama — and even carried clues to a person’s village or status. Tattooing was performed by female specialists using bundles of needles dipped in black ink. Women gathered together for the ritual, often singing Hajichi songs to soothe the pain, while men played music in support. It was a community act — a declaration of belonging.

But that belonging would soon be challenged.

⏾Ink as Crime: The Colonial Suppression of Hajichi

In the late 19th century, Japan formally annexed the Ryukyu Kingdom, renaming it Okinawa Prefecture. What followed was a brutal campaign of assimilation and cultural erasure, framed under the rhetoric of “modernization.”

The Meiji government viewed Hajichi as primitive, unsightly, and shameful. In 1899, it issued the “Irezumi Ban Order” in Okinawa — part of a broader project to cleanse Japan of what it saw as non-Yamato (non-mainland) customs. Ryukyuan women were arrested, fined, or publicly shamed for their tattoos. Some were even deported from overseas work assignments, labeled as national embarrassments.

Over 690 women were arrested in Okinawa between 1899 and 1903 — compared to just 40 in Tokyo during the same period. The stark difference made clear: this was not about public hygiene or aesthetics, but about control over indigenous identity and the female body.

Women responded in complex ways. Some hid their hands behind long gloves. Others attempted to erase their marks with acid or have them removed in hospitals. But many resisted quietly — continuing to tattoo each other in sugarcane fields, behind homes, in the dark, keeping the ritual alive, even in fragments.

⏾Gendered Colonization: Controlling Women’s Bodies

The suppression of Hajichi was not just a cultural loss — it was also a gendered act of colonization.

By targeting tattoos worn exclusively by women, the state asserted dominance over both ethnic identity and feminine agency. The Meiji state sought to impose a Yamato ideal of womanhood: modest, educated, non-threatening. Ryukyuan women — with their strong matrilineal traditions, spiritual roles, and visibly marked hands — defied this image.

Erasing Hajichi meant reshaping the Ryukyuan woman into something legible to empire: modern, silent, unmarked.

This pattern echoes other colonial projects across Asia — including the banning of Ainu mouth tattoos, Chinese footbinding, and Taiwanese indigenous tattoos. In each case, the body of the woman became a site of occupation — its traditions pathologized, its adornments criminalized.

⏾A Tattooed Afterlife: Remembering Hajichi Today

By the 1940s, Hajichi had nearly disappeared. World War II ravaged Okinawa, and much of its material culture — photos, texts, and oral histories — was lost.

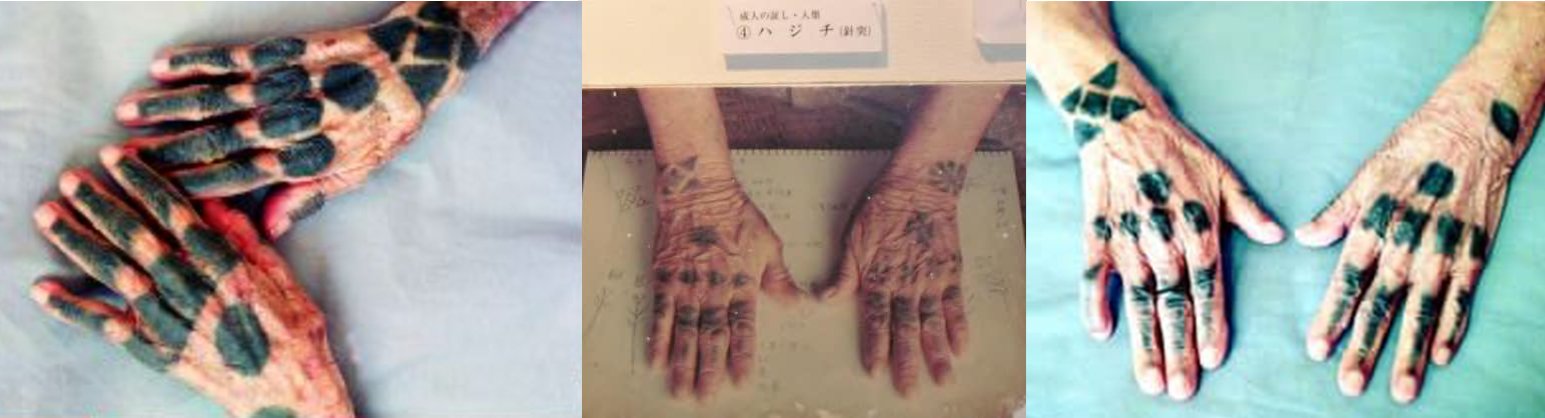

But starting in the 1980s, researchers and cultural workers began collecting stories from the last living women who bore Hajichi. Over 2,000 women were interviewed. Many wept as they recounted the shame they were made to feel — and the pride they still quietly carried. Others remembered being told as girls that without Hajichi, they would be taken to Yamato — an ominous prophecy that became real.

In recent years, artists and activists have begun reviving Hajichi, not as direct replicas, but as modern acts of remembrance. Some incorporate the motifs into nail art, fashion, or contemporary tattoos. Others create digital archives, music recordings, or silicone models of tattooed hands for exhibitions. These are not nostalgic gestures — they are acts of cultural sovereignty.

⏾Why It Matters

Tattoos by Moeko Heshiki’s Hajichi Project (https://www.instagram.com/hajichi_project/?hl=en)

Hajichi is a reminder that tattoos are never just skin-deep.

They are memory. Identity. Resistance. For the Ryukyuan women who bore them, Hajichi was a source of dignity — even when the state, society, and history tried to erase them.

As tattoo culture continues to evolve in Japan and globally, it’s essential to remember those whose marks were criminalized, hidden, and nearly forgotten. Their ink lives on — not only in faded skin, but in archives, stories, and the bodies of those reclaiming their past.

Want more content like this? Follow the InkSmith Journal for stories at the intersection of tattooing, history, culture, and resistance.

To learn more about the evolution of mainland Japanese tattooing, from its Edo-era woodblock roots to its entanglement with underground culture, check out our companion post: The Evolution of Irezumi: From Penal Markings to Masterpieces of Art

And if you're feeling inspired to start your own tattoo journey, whether you're drawn to classic motifs or modern interpretations, our artists are always available for consultation.