The Evolution of Irezumi: From Penal Markings to Masterpieces of Art

Few artistic traditions are as deeply intertwined with history, rebellion, and devotion as irezumi, Japan’s tattooing practice. Though today’s large-scale bodysuits and intricate motifs are admired for their craftsmanship, irezumi has a long and complex history. One that spans criminal punishment, the floating world of courtesans, and the rise of outlaw heroes. In this piece, we explore the transformation of Japanese tattooing, from a symbol of infamy to a revered art form.

⏾ Ancient Beginnings and Criminal Markings

Jomon period clay (14,000 and 300 BC) figures with tattoo markings.

The origins of tattooing in Japan stretch back centuries, with early accounts of facial and body tattoos appearing in Chinese records describing the Wa people of ancient Japan. These marks initially had spiritual and social significance, possibly denoting status or protection.

However, by the Edo period (1603–1868), tattooing had become a tool of punishment to ensure exile from society. The irezumi no kei (刺青の刑), or "tattoo penalty," varied by region. Criminals were tattooed with kanji characters or geometric marks on their faces, arms, or backs as a permanent mark of shame.

Criminal Tattoo Markings.

For example:

Foreheads were marked with the kanji for "dog" (犬) for severe crimes.

Some regions branded criminals with horizontal lines across their arms, with each offense adding a new line.

In others, boar hunters and outcasts (eta class) were also forcibly tattooed, marking their social status.

As time passed, however, many of those branded sought to reclaim their bodies. Rather than live with shame, they transformed their punishment tattoos into elaborate designs, thus beginning the shift from penal markings to artistic expression.

⏾ Ancient Beginnings and Criminal Markings

The 18th and 19th centuries witnessed a dramatic evolution in Japanese tattooing. One of the biggest influences came from ukiyo-e (woodblock prints), a popular art form that depicted samurai, kabuki actors, and mythical heroes in vividly colored scenes.

Toyohara Kunichika. Actors Ichimura Kakitsu IV as AsahinaTobei, Nakamura Shikan IV as Washi no Chokichi, and Sawamura Tossho II as Yume no Ichibei , 1868. Photo: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

A pivotal moment came with the Japanese translation of the Chinese novel Water Margin (Suikoden), which depicted 108 outlaw heroes, some of whom were tattooed warriors fighting against corruption (We have touched on this briefly in our article about Chinese Caligraphy Tattoos). These illustrations, particularly those by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, brought full-body tattoos into mainstream admiration. The intricate designs of dragons, tigers, and deities inked onto these fictional warriors captivated Edo-period audiences, inspiring real-life imitations.

Tebori (手彫り) a traditional Japanese hand-poked tattooing technique where artists use a rod with attached needles to manually insert ink into the skin, creating rich, smooth gradients and deep color saturation.

Around this time, the horishi (彫師 tattoo masters) emerged, refining techniques such as tebori (手彫り), the traditional hand-poking method that remains revered today. Many of these tattooists were former woodblock carvers, applying their engraving expertise to skin instead of paper. The distinct shading technique, bokashi (ぼかし / 暈し), allowed for seamless gradient fades — a hallmark of traditional irezumi (刺青 / 入れ墨).

By the late Edo period, tattoos were no longer just for criminals. Firefighters, laborers, and even merchants adorned their bodies with irezumi, both as protective charms and symbols of personal strength.

⏾ Courtesans, Love Tattoos, and Forbidden Desire

While irezumi is often associated with men, tattooing was also deeply embedded in the world of courtesans and lovers. During the Edo period, tattoos became symbols of passion and devotion. Lovers would engrave each other’s names on their bodies, usually on the inner arm or thigh, accompanied by the ideogram "inochi" (命 / いのち “life" or "fate," often used in poetic or philosophical contexts), signifying eternal love. Some took it further, incorporating motifs like umbrellas (aiaikasa 相合傘), meaning "love under an umbrella"), symbolizing a shared fate.

Courtesans, particularly those in the pleasure districts of Yoshiwara and Shimabara, sometimes had tattoos dedicated to their favored clients. One famous case was Otama, a high-class courtesan who tattooed the family crests of her warrior-class lovers until her entire body was covered. Love tattoos were not without risk—some courtesans, once abandoned, sought painful removals, often using acid or burning the skin.

These practices were not limited to women. Men, too, marked their bodies for love, believing that love tattoos enhanced their seductive appeal. Satirical poems (senryu 川柳) from the era even mock men who flaunted these markings to impress lovers.

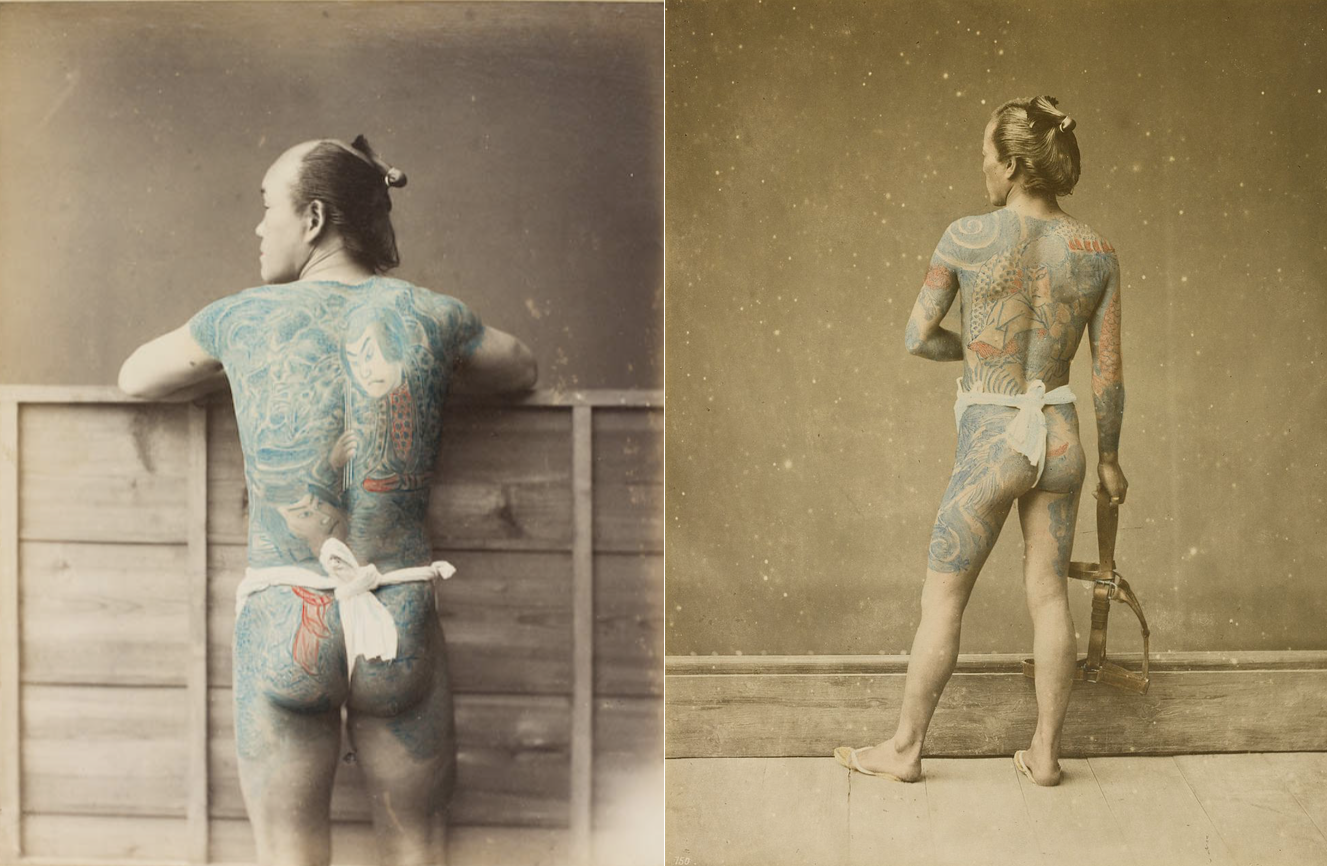

Photograps by Raimund Stillfried von Rathenitz, 1850

⏾ Meiji Era Suppression and Western Obsession

By the Meiji Restoration (1868–1912), Japan was eager to modernize and gain Western respect. To appear more “civilized,” the government banned tattooing in 1872, considering it a mark of barbarism. Yet, ironically, Western royalty and adventurers flocked to Japan to get traditional irezumi.

One of the most famous cases?

King George V of England (then a prince) got a full Japanese dragon tattoo on his arm in 1881. His cousin, Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, followed suit.

The Last Czar, Nicholas II's, Dragon Tattoo in Real Life

So while Japanese tattooing was outlawed for its own people, it became a luxury sought after by European elites. A paradox that still echoes today.

⏾ Kabuki, Yakuza, and the Criminal Stigma

Despite its growing popularity, tattooing was still viewed with suspicion, particularly among the samurai elite, who saw it as a mark of the lower classes. Kabuki theater played a significant role in furthering the romanticized image of the tattooed rogue. Famous actors portrayed iro-aku (色悪 / いろあく charming villains), bad-boy figures whose rebellious spirit captivated audiences. By the Meiji era (1868–1912), the government banned tattooing entirely, associating it with criminal activity.

This forced the practice underground, where it became linked to the yakuza (Japanese organized crime). Many gangsters adopted full-body tattoos, often covering them with clothing, revealing their ink only in private bathhouses or ritualistic gatherings.

⏾ Irezumi in the Modern Age

Despite legalization in the post-WWII era, irezumi still faces deep-rooted stigma in Japan today. Even today, irezumi carries this historical weight. Many onsen (hot springs) and other public facilities in Japan still forbid tattooed individuals, a remnant of past associations with organized crime.

Despite its fraught history, irezumi is experiencing a resurgence. While still somewhat taboo in Japan, many artists are working to preserve its legacy, blending traditional methods with modern influences. Outside Japan, irezumi is widely celebrated, attracting collectors worldwide who admire its meticulous technique and storytelling power.

Master tattooists, including those following the Horibun (彫文/ほりぶん) and Horiyoshi (彫義/ほりよし) lineages ("Hori" (彫) prefix, which means "to carve/engrave," is commonly used by master tattooists in Japan), continue to practice the art, ensuring its survival. Japanese tattoo masters are revered worldwide, and styles like sleeve tattoos (nagasode 長袖刺青 / ながそでいれずみ), backpieces (senaka 背中刺青 /せなかいれずみ), and bodysuits (munewari 胸割り刺青 / むねわりいれずみ) remain highly sought after.

Irezumi Tattoos by Calvin at InkSmith Tattoo Singapore

Tattooists like Calvin at InkSmithTattoo Singapore are part of a new generation keeping the craft alive—blending old-world technique with contemporary vision.

As attitudes shift and appreciation for Japanese tattooing grows, irezumi is reclaiming its status. Not as a mark of defiance, but as a masterpiece of living art.

(For those interested in indigenous Japanese tattoo traditions, including the Ainu and Ryukyuan, we will cover these in a future entry. Stay tuned!)

Are you looking to get a traditional irezumi piece in Singapore? Book a consultation with Calvin and discuss your vision with an artist who respects the legacy of Japanese tattooing while bringing his own bold, distinctive touch to the craft.